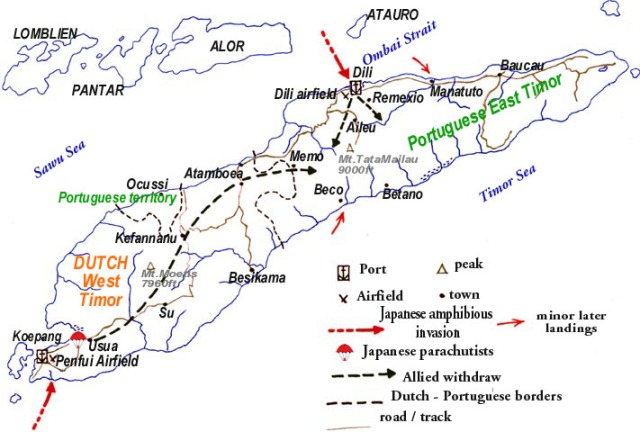

Australian guerrilla troops with Timorese, 1942

Years before the Pacific war broke out it was obvious to both the Australians and the Dutch that the Japanese would want to grab the resource rich Dutch dominions. And it took no crystal ball to predict the conquest of Australia and New Zealand as the next step…

A secret agreement was drawn up between the Dutch and the Australians in which they agreed that, when Japan attacked the Netherlands East Indies, Australia would send forces to reinforce the Dutch on Timor and Ambon.

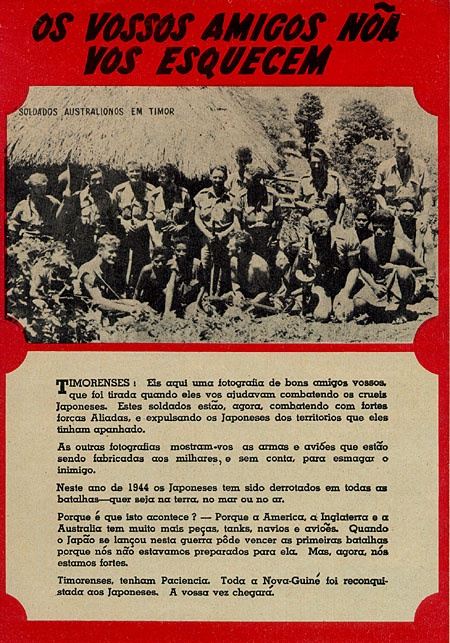

Timor was a special case as it was divided between the Dutch and the Portuguese. Knowing the Portuguese would not fight the Japanese the Dutch decided to defend the Portuguese part of the island. The Australians would defend the Dutch part.

Thus, when the Pacific war broke out on December 7, 1941, the Australian government hurriedly assembled what was to be known as “Sparrow Force”, 2/40th Battalion, 23rd Brigade AIF commanded by Lt. Col. ‘Bill’ (later Sir William) Leggatt. Attached was, 2/2nd Independent Company, led by Major (later Lt. Colonel) Alexander Spence. A predominantly West-Australian commando unit specifically trained in ‘stay behind’ operations and guerrilla tactics. They were hurriedly taken aboard two of the ships available in the port, the transport SS Zealandia and the armed cruiser HMAS Westralia, actually a hastily converted passenger liner. The ships departed Darwin in the morning of 10 December 1941 and reached Kupang without incident two days later. They reinforced the Dutch garrison on the island, consisting of 600 KNIL troops, commanded by Lt.Col. ‘Nico’ van Straten. Being an infantry unit, they were lightly armed; their heaviest weapons were four 75mm field guns.

The Royal Netherlands Navy (RNN) vessel “Soerabaja” was sent to Kupang with orders to ferry the Dutch troops to Portuguese Timor. During the night of 15 December, a detachment of 200 Dutch and 200 Australian troops (including a Dutch and an Australian negotiations officer) boarded the old ship.

Map of the Japanese invasion of Timor and Allied movements, early 1942

When the ship arrived off the coast of Dili on 17 December, pure slapstick comedy followed. The negotiations officers went ashore to ask the Portuguese governor, Manuel de Abreu Ferreira de Carvalho, for permission to land the troops. The governor protested and stalled for time, anxiously trying to get instructions from his government – over a very shaky telegraph line and half a world away…

By mid-day the soldiers lost their patience and “Soerabaja” anchored 100 yards off the Dili coast, disembarking its troops while both “Soerabaja’s” 28cm guns were manned and ready to intervene.

The Portuguese governor declared himself prisoner and the Portuguese dictator, Antonio de Salazar, protested with the Allied governments. However, the 500 Portuguese government troops did not interfere. And the Portuguese colonists as well as the Timorese civilians welcomed the allies. In January 1942 most of the KNIL soldiers under Van Straten and the whole of the 2nd Independent Company under Major A. Spence had been transferred to Portuguese Timor where they were dispersed over the area in small groups.

The loss of Timor

Timor soon became a key link in the so-called “Malay Barrier”. Penfui airfield in Dutch Timor was a key air link between Australia and American forces fighting in the Philippines under General Douglas MacArthur. Initial Japanese air attacks on Penfui were hampered by AA fire and American P-40’s operating out of Darwin.

By January 1942,, many members of Sparrow Force—most of whom were unprepared for tropical conditions—were suffering from malaria and other illnesses. On 12 and 16 February more reinforcements arrived in Kupang. Among the new arrivals were 189 British anti-aircraft gunners, belonging to A & C Troops of the Royal Artillery 79th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, most of whom were veterans of the Battle of Britain. Another new arrival was Brigadier W. Veale, Commanding Officer Allied Forces Timor, and his staff.

Later on 16 January, an Allied convoy loaded with reinforcements (the Australian 2/4th Pioneer Battalion and the 49th American Artillery Battalion) as well as supplies was approaching Kupang. It was escorted by the heavy cruiser USS Houston, the destroyer USS Peary, and the sloops HMAS Swan and Warrega. Close to the Timor coast the ships came under intense Japanese air attack and were forced to return to Darwin without landing. The Sparrow Force would not be reinforced further.

On the night of 19/20 February 1,500 troops from the Imperial Japanese Army’s 228th Regimental Group, which formed part of the 38th Division, XVI Army, under the command of Colonel Sadashichi Doi, began landing in Dili. The garrison withdrew, their retreat covered by the 18-strong Australian commando No. 2 Section stationed at the airfield. During this rear-guard action the commandos killed an estimated 200 Japanese in the first hours of the battle. Interesting detail: the Japanese army recorded its casualties as only seven men but ative accounts of the landings support the Australian claims…

Another group of Australian commandos, No. 7 Section, was less fortunate. They drove into a Japanese roadblock by chance and all but one of them were summarily executed by the Japanese.

On the same night, the main body of the 228th Regimental Group (4.000 strong) landed at the Paha River on the undefended southwest side of the island. They rapidly advanced north, cutting off the Dutch positions in the west. When they attacked the 2/40th Battalion positions at Penfui, Leggatt ordered the destruction of the airfield and a retreat towards the Usua ridge in the east. This move placed the 2/40th in the right spot to intercept Koichi Fukuma’s 3rd Yokosuka Paratroopers as they descended into fields near Usua, 22 km (14 mi) east of Kupang. They landed right in the middle of the Aussie hornets’ nest and more than half of the unlucky paratroopers were killed by gunfire or bayonets. A second airdrop of 300 paratroopers, made Sparrow Force leave the village of Babau by the night of the 21st. They planned to move eastward in the morning.

By then, the Japanese had dug in defensive positions on Usua Ridge with a mountain howitzer and heavy machine guns near the road. However, after a mortar and machine gun barrage, the entire Australian force attacked. Captain Johnson, Captain Roff and Captain Burr (their platoons reinforced by gunners, sappers and engineers) led a bayonet charge up the ridge. In this furious assault, the Sparrow Force killed all but 78 of the 850 paratroopers while it suffered only a few dozen losses.

Enraged by these unexpected heavy losses the main Japanese force of about 3,000 men attacked the Australians with tanks and artillery. By the morning of 23 February, Sparrow Force was out of food and water, low on ammunition, weary from little sleep and hopelessly outnumbered. Leggatt surrendered at Irekum on 23 February. The 2/40th Battalion had suffered 84 killed and 132 wounded in the fighting, while more than twice that number would die as prisoners of war during the next two and a half years.

Veale and the Sparrow Force HQ —including about 290 Australian and Dutch troops—continued their trek eastward across the border, to link up with the 2/2 Independent Company. Outnumbered, the survivors of 2/2 had withdrawn to the south and to the east, into the mountainous interior. And Van Straten and his 200 remaining KNIL troops had headed southwest toward the border.

The commando campaign

On 8 March 1942 General Ter Poorten surrendered to the Japanese on Java and had a message broadcast ordering all Allied troops in Java to cease fighting. Surviving forces on other islands disregarded the message and continued the fight against the invaders.

By mid-March 1942 Van Straten and his surviving KNIL forces on Timor and survivors of ‘Sparrow Force’ teamed up with the remaining members of 2/2 Independent Company. Deeply hidden in the thick Timor jungle the CO’s took stock. Their combined force would soon attract a Japanese attack which they knew they could not win. Unwilling to give up the fight they decided to start a guerrilla campaign.

They split up in teams of eight or nine men and, dispersed throughout the mountains of Portuguese Timor, the commandos commenced their raids against the Japanese.

During the early months, the success of the guerrillas in East Timor was only made possible by this support they received from the local Timorese who, risking execution by the Japanese, acted as porters and guides and provided food and shelter.

Portuguese officials remained officially neutral and in charge of civil affairs but both the Portuguese and the indigenous East Timorese were usually sympathetic to the commandos. Still able to use the local telephone system to communicate among themselves they gathered intelligence on Japanese movements.

Timorese and Australian commandos – The Timorese went out of their way to help the Australians. Sadly, many of them paid for it with their lives…

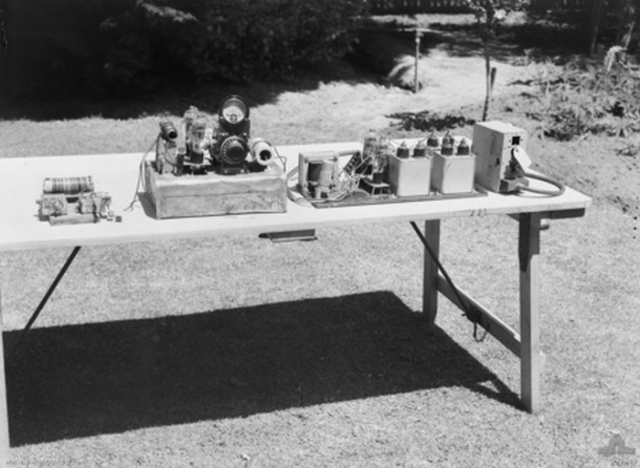

The big problem however was that, since Leggat’s surrender on 23 February, the survivors of “Sparrow Force” did not have any functioning radio equipment and thus were unable to contact Australia to inform them of their continued resistance.

Major Spence directed Captain George Parker to get a radio somehow. Taking stock he found that work was already underway. Signaller Max (“Joe”) Loveless was trying to cobble together a primitive radio. To support him, Parker ordered his teams to ‘collect’ as much radio equipent as possible. And so they did.

One team raided the big SAPT plantation in Fatu Besi and brought back a receiver set. Corporal Alan Donovan and a team of three brought back other parts, including the crystals from a destroyed Australian set. On 1 April, they had enough components and “Joe” Loveless went to work in earnest. Two weeks later – after solving a series of major problems, such as how to charge batteries in an out of the way shed in the jungle – Loveless transmitted his first message on 19 April 1942

His call sign – YCF – had been made redundant after the fall of Timor and Captain Joseph Honeysett, senior signals officer on duty in Darwin that night suspected a Japanese ruse. He first had all transmitting stations in the neighbourhood shut down to prevent interference with the weak source. Next, he wanted to have proof of identity. One of the signallers on the Darwin team said he knew a sergeant named Jack Sargeant on the ‘Sparrow Force’ team. Honeysett nodded and listened while his signaller interrogated the other guy.

Darwin: “Do you know Jack Sargeant?

Sparrow Force: “Yes, he is here with us.”

Darwin: “Is he there? Bring him to the transmitter. Tell us your wife’s name, Jack, right now!”

Sparrow Force: “Kath.”

Then Sargeant also correctly answered a question about his street address and Honeysett knew that this was Jack Sargeant and that it was not a Jap ruse. He asked for a report. The response was completely unexpected and has secured a place in Australian military history.

“The Timor force is intact and still fighting. Badly need boots, quinine, money and Tommy gun ammunition.”

Next night, supplies were dropped by a RAAF Hudson and the men in the Timor jungle proudly called Lovell’s cobbled up radio “Winnie the War Winner“, a name partially borrowed from a popular wartime cartoon character.

Once supplies began to arrive the morale and spirit of the troops became very high. They intensified their raids and the Japanese were forced back into their strongholds at Dilli and the other main towns, leaving the rest of Portuguese Timor to the guerrillas.

Annoyed by the continuing resistance Colonel Sadashichi Doi, the Japanese commander in Timor, sent the Australian honorary consul, David Ross (also the local Qantas agent) to find the commandos and pass on a demand to surrender. To which Spence responded: “Surrender? Surrender be fucked!“

Ross came back carrying a note in Portuguese and intended for the Timorese, stating that anyone supplying the commandos would be later reimbursed by the Australian government. And after his return the ambushes and raids continued and intensified.

Exasperated, the Japanese high command sent a highly regarded veteran of the Malayan campaign and the Battle of Singapore to Timor. He was a major known as the “Tiger of Singapore” (or “Singapore Tiger”; his real name is unknown).

On 22 May, the “Tiger”—mounted on a white horse—led a Japanese force towards Remexio. An Australian patrol, with Portuguese and Timorese assistance, staged an ambush and killed four or five of the Japanese soldiers. During a second ambush, Ray Aitken (an Australian sniper) shot and killed the “Tiger”. Another 24 Japanese soldiers were also killed, and the force retreated to Dili

During May 1942, Australian aircraft were dropping supplies to the commandos and their allies. However, the rugged terrain hampered the drops and only one in three was successfully retrieved. The Australians decided to change tactics and on May 24, a US Navy Catalina piloted by Lt. ‘Tom’ Moore landed on the south east coast and unloaded much needed supplies and … mail. Also on board was a list of promotions. Spence was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and appointed CO.

The Catalina left, evacuating the now redundant Veale and Van Straten as well as five wounded, including private Craighill whose jaw had been shot off…

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) was made responsible for supplying the campaign with 40 tons of supplies per month. The patrol vessel HMAS Kuru (55 tons) commanded by reserve Lieutenant Joseph Joel arrived at a beach in Betano Bay on May 27th 1942, with ten tons of ammunition, medical supplies, food and clothing that was unloaded by midnight. On her trip back to Darwin the Kuru took aboard some wounded men. In July the ex-customs patrol vessel HMAS Vigilant (106 tons) commanded by sub-lieutenant Allan Bennett joined the Darwin-Timor run.

The chief of the Australian Army, General Sir Thomas Blarney, trained in conventional warfare, completely failed to grasp the significance of the news about the commandos still fighting in Timor. On 11 June he recommended General Douglas MacArthur to withdraw the commandos or organize some kind of more ‘regular’ warfare on Timor.

MacArthur did not know precisely what the commandos were doing but he immediately grasped their value. They tied up Japanese troops, thus preventing them from being used elsewhere. In his reply he stated firmly that ‘… these forces should not be withdrawn!’

In June 1942, Colonel Doi once again sent Ross with a message, complimenting Sparrow Force on its campaign so far, and again asking that it surrender. The Japanese commander drew a parallel with the efforts of Afrikaner commandos of the Second Boer War and said that he realized it would take a force 10 times that of the Allies to win. Nevertheless, Doi said he was receiving reinforcements, and would eventually assemble the necessary units. Having delivered his message, Ross did not return to Dili this time. He was evacuated by Catalina to Australia on 16 July.

The Japanese offensive

The commander of the Japanese 48th Division, Lieutenant General Yuichi Tsuchihashi arrived early August to assume control of operations on Timor. He sent a threatening message to the men of Sparrow Force , containing the phrase “you alone do not surrender to us!”

That August, Japanese forces began to burn and/or bomb villages believed to have assisted the Allies, causing huge civilian casualties. During September the main body of the Japanese 48th Division began arriving to take over the campaign.

The Australians also sent reinforcements on September 23. The 450-strong 2/4th Independent Company known as Lancer Force was sent over aboard the destroyer HMAS Voyager. During debarkation the vessel ran aground in the bay of Betano and had to be abandoned after it came under air attack.

By October the Japanese had succeeded in ‘recruiting’ significant numbers of Timorese civilians, who suffered severe casualties when used in frontal assaults against the Allies. The Japanese had also ordered all Portuguese civilians to move to a “neutral zone” by November 15. Those who failed to comply were to be considered accomplices of the Allies. This succeeded only in encouraging the Portuguese to cooperate with the Allies, whom they lobbied to evacuate some 300 women and children. At least 26 Portuguese civilians were killed in the first six months of the occupation, including local officials and a Catholic priest

Spence was evacuated to Australia on November 11, and the 2/2nd commander, Major Bernard Callinan was appointed Allied commander in Timor. On the night of November 30-December 1, the RAN mounted a major operation, to land fresh Dutch troops based in Australia at Betano, and evacuate 190 Dutch soldiers and 150 Portuguese civilians. The launch HMAS Kuru was used to ferry the passengers between the shore and two corvettes, HMAS Armidale and HMAS Castlemaine. However, the Armidale, carrying the Dutch reinforcements, was sunk by Japanese aircraft — almost all of those on board were lost.

On December 11-12, the remainder of the original Sparrow Force, except for a few officers, was evacuated with some Portuguese civilians, by the Dutch destroyer HNLMS Tjerk Hiddes.

By this time the chances of an Allies re-taking Timor were remote, as there were now 12,000 Japanese troops on the island and the commandos were coming into increasing contact with the enemy.

In the first week of January, the decision was made to withdraw Lancer Force. On the night of January 9-10, the bulk of the 2/4th and 50 Portuguese were evacuated by the destroyer HMAS Arunta. A small intelligence team known as S Force was left behind, but its presence was soon detected by the Japanese. With the remnants of Lancer Force, S Force made its way to the eastern tip of Timor, where the Australian-British Z Special Unit was also operating. The remaining Allied forces were evacuated by the US Navy submarine USS Gudgeon on February 10.

Flyer left behind by the commandos of “Lancer Force” telling the Timorese their friends will nor forget them

The commandos and their civilian allies had prevented an entire Japanese division from reaching the New Guinea campaign. However, this had come at a high price, which included the deaths of 40,000 to 70,000 Timorese civilians.

Great story, Robert, Knew the basic story but not these1. details

LikeLike

Thanks Ian. Glad you like it. And it IS a great story, unfortunately too little known.

LikeLike

Great unknown story ! Keep your great work moving Ian .

Saluut !

LikeLike

Thanks Johnny.

More post coming soon.

Robert

LikeLike

My father in law Leendert Thomas was one of the Dutch Guerrillas on Timor.

Wouneed twice, but survived.

Wis I knew more about his service.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Barry,

People like your father in law were really tough guys. And my experience is that they seldom – if ever – talk about their wartime experiences. Sometimes the effort of getting information out of them is like trying to open an oyster with a limp knife. I think they’ve seen too much and suffered too much to talk about it.

What I am trying to do is give them at least the ‘place in the sun’ they deserve. They are too often ‘Forgotten Heroes’

Thanks for reading my blog and for commenting.

Robert

LikeLiked by 1 person

Barry, I am researching Dutch soldiers who fought on Timor in 1942, including Leendert Thomas (his service number was 80215, born May 8th 1915) please contact me at

timor1942project@gmail.com

Regards, Brad Z.

LikeLike

Barry, I am doing research in Australia on behalf of a project in the Netherlands about the Dutch Timor guerillas, including your father in law. From what I have Leendert was born May 8th 1915, and was in Brisbane at some point during the war.

I’d love to get in touch with you; the projects email address is timor1942project@gmail.com

Regards, Brad

LikeLike

Outstanding work on your part! This is a subject that I have NEVER seen covered in books on the Pacific/ S.E. Asia theatre in WWII.

The courage of these soldiers and their civilian allies is amazing under the circumstances they were in. Their contribution was significant and sadly overlooked.

Thank you for telling their story.

LikeLike

Wow, thank you for such a great story. Just today I was with my Aunty going over my grandfathers notes about his time during the war and in detail his experiences in Timor fighting the Japanese and working with the Australians. Opa’s transcripts are that they were shipped to Kupang on the 15th of December 1941. Unable to disembark they then travelled to Dili.. Opa mentions the 300 Australian “Independent” troops arriving and moving inland. He says the Australians trained the Dutch lads in guerrilla warfare. In Feb 1942 he talks of intense fighting against great numbers of Japanese and shrapnel wounds. They stole horses and road bareback for 13 days through the mountains before making contact with the Australian guerilla troops who restored their health. Much more to his story. Opa and his mates were eventually found by the Japanese after locals gave away there position. Then his story moves onto Changhai and the railway. He makes mention of Nico Van Straten as well in his letter to his family in Holland.

LikeLike

Thanks Jo, for your comments. It was a bad time and your granddad must have been a tough character to survive all this.

LikeLike